By Kizito CUDJOE

The central bank is facing calls to tread carefully as it rolls out new reforms for the microfinance and rural banking sector, amid concerns that poor execution could unsettle a sub-sector that has only recently regained public trust.

The Bank of Ghana (BoG) has introduced revised guidelines under a new microfinance framework aimed at strengthening capital adequacy, improving resilience and accelerating modernisation to deepen financial inclusion.

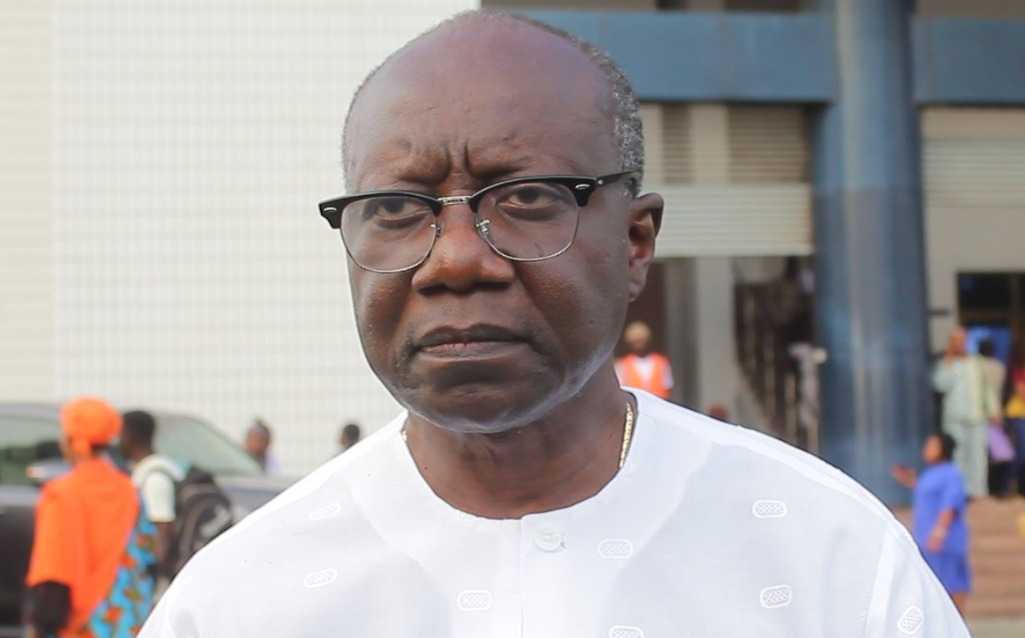

However, rural banking expert Mr. Joseph Akossey warns that while the policy direction is sound, weak communication or abrupt implementation could undermine depositor confidence and reverse gains made since the financial sector clean-up.

Rural and Community Banks (RCBs) have recorded improvements in deposits, asset growth and profitability over recent years – with several returning to the Ghana Club 100 rankings, a development he said reflects renewed public confidence.

“If implementation is not carefully managed, it could trigger uncertainty across the financial ecosystem,” Mr. Akossey said, citing one rural bank that recorded deposits of about GH¢2.3billion in 2025 as evidence of rising trust in the sub-sector.

He urged the central bank to prioritise stakeholder engagement and public education as the reforms take effect, warning that confidence, once shaken, is costly to rebuild.

Why confidence may matter more than capital in BoG rural bank reforms

BoG’s renewed push to strengthen the microfinance and rural banking sector reflects lessons from the country’s financial sector clean-up. Yet for Rural and Community Banks (RCBs), the reforms’ success may depend less on regulatory intent and more on how the changes are communicated and sequenced.

RCBs were among the most affected institutions during the 2017-2019 clean-up, a period that left deep scars on depositor confidence – particularly in rural communities. In recent years the sub-sector has however staged a quiet recovery, posting improved profitability, growing deposit bases and stronger balance sheets.

This recovery makes the current reform moment unusually sensitive.

“The objective of the reforms is noble, but execution will determine whether they strengthen or destabilise the sector,” said Mr. Akossey, the Executive Director of Proven Trusted Solutions.

One rural bank’s GH¢2.3billion deposit base in 2025, he noted, underlines how far confidence has returned. Any perception that reforms signal distress could quickly reverse that trend.

Communication gap

A central risk identified by industry watchers is the communication strategy around the reforms. While the BoG has initiated public education efforts, including televised documentaries, Mr. Akossey said the approach may not adequately reach the core clientele of microfinance institutions.

Most rural banking customers operate in informal and semi-formal settings, where information spreads quickly but is often shaped by rumours rather than official clarification. Mr. Akossey argued that limiting education campaigns to English-language broadcasts risks excluding the very audience these reforms are meant to protect.

He therefore called for sustained, multilingual communication across radio, community platforms and frontline banking staff to prevent misinformation from taking hold.

Capital pressure and structural constraints

Under the revised framework, RCBs that wish to operate independently must meet a GH¢5million minimum capital requirement while others are encouraged to merge.

Some banks may attempt to meet the threshold by converting retained earnings into share capital, but Mr. Akossey cautioned that this does not inject fresh liquidity and could dilute earnings per share. Banks may also face tax obligations on bonus shares, further complicating the strategy.

He urged RCBs to pursue proactive share mobilisation including attracting new investors and convincing existing shareholders to deepen their stakes, rather than waiting for regulatory deadlines.

Locked-up funds and policy choices

Another unresolved issue is funds still trapped in defunct financial institutions following the clean-up. Some RCBs impaired these investments, weakening reserves and constraining their ability to recapitalise.

Fast-tracking the release of such funds, Mr. Akossey argued, would immediately strengthen balance sheets and reduce pressure on otherwise viable banks.

He also pointed to the precedent of Ghana Amalgamated Trust (GAT), which supported solvent but undercapitalised indigenous banks during the clean-up. A similar mechanism, he said, could be considered for merged RCBs that remain profitable but capital-constrained.

Recent unaudited results suggest the sector has capacity to repay such support, with some rural banks posting profits above GH¢90million and others exceeding GH¢200million.

Why it matters

RCBs remain the backbone of financial intermediation in many communities where larger commercial banks see limited commercial appeal. Any disruption to their operations could widen financial exclusion and weaken credit flows to agriculture, small enterprises and households.

For the BoG, the challenge is not whether reform is needed but how it is delivered. “Confidence is the invisible capital of rural banking,” Mr. Akossey said. “Once it is lost, no amount of regulation can replace it.”

The post RCB reforms pose confidence test for BoG appeared first on The Business & Financial Times.

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS