Lucie was just seven years old when the men took her. She was found the next day, naked and bleeding, on the edge of the vast forested hills of Kahuzi Biega Park, in violence-plagued eastern DR Congo.

"The militants entered the family home during the night," said her mother Adeline, recalling the day that her family was touched by the terror that gripped their small village as militiamen abducted and raped dozens of girls, some barely more than babies.

Lucie's injuries were so serious she was taken to Denis Mukwege.

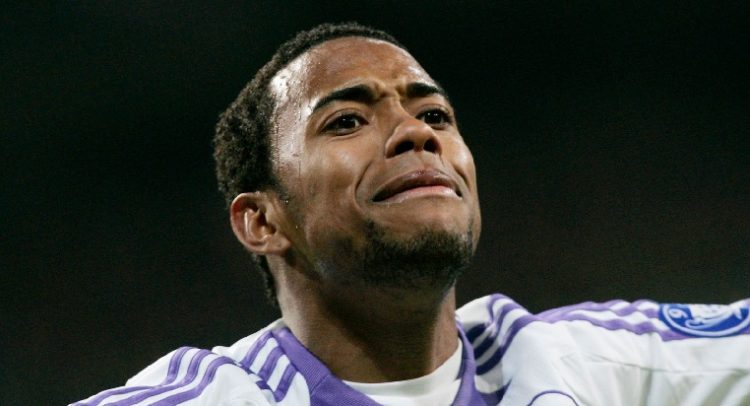

Known as "Doctor Miracle", 2018 Nobel Peace laureate Mukwege has treated thousands of women and girls brutalised in the country's lacerating conflicts.

"She had several operations for two months," Adeline told AFP, in a secluded hut where she spoke alongside other mothers of victims of the three years of violence against girls in their village of Kavumu.

A total of 42 girls, aged between 18 months and 12 years, were abducted by the Djeshi ya Yesu militia, or "Army of Jesus", between 2013 and 2016 in Kavumu, in the province of South Kivu.

Many were taken to Mukwege.

At his Panzi hospital in Bukavu, the provincial capital of South Kivu, the doctor performs reconstructive surgery on women and girls who have suffered serious internal injuries.

"It was very hard, for me and all the staff. I have never before seen people weeping while they were tending" to patients, he told AFP in a weekend interview ahead of accepting the Nobel award on Monday.

"I believe that in my life I have never been as disturbed, shocked, I don't have the words. When you see an innocent little baby, but bloody, with their genitals shredded, you ask yourself questions about humanity.

"How could we get to this point? What happens to humans who have no rules? It has no limit."

Justice fight

Nobel Peace laureate Mukwege has treated thousands of women and girls brutalised in the country's lacerating conflicts. By Alain WANDIMOYI (AFP/File)

Nobel Peace laureate Mukwege has treated thousands of women and girls brutalised in the country's lacerating conflicts. By Alain WANDIMOYI (AFP/File) Once Mukwege has staunched bleeding and rebuilt battered bodies, his focus turns to justice.

Panzi's Legal Clinic, which provides forensic evidence and legal representation, took part in the trial against a provincial lawmaker and 10 militiamen who were convicted last year over the Kavumu abductions and rapes and sentenced to life in prison.

The UN's peacekeeping mission in the country hailed the landmark case as a "major advance in the fight against impunity for sexual violence".

The trial also provided $5,000 (4,390 euros) in compensation for each of the victims -- although the families say they still have not received anything.

Around 40 cases are ongoing -- either as complaints filed or trials.

Efforts to bring an end to impunity for sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo began to gather pace in 2011, when nine soldiers were convicted by a military court for ordering and carrying out mass rapes.

About 60 women were raped in one night that year in the town of Fizi, some 250 kilometres south of Bukavu.

Lieutenant Colonel Kibibi Mutware, two majors and a second lieutenant were sentenced to 20 years in jail for "crimes against humanity by way of rape and other inhuman and terrorist acts".

Armed groups vying for control of the region's vast mineral wealth often use mass rape to terrorise the local population.

Violence is again on the rise with the proliferation of armed groups since 2016 as the country's political situation became increasingly unstable.

Mukwege said up to seven percent of rape victims at his hospital are now infants -- up from around three percent.

"It is enormous that it is the children who are targeted by such acts. But this as well is the consequence of impunity," he said.

Fears for 'little sisters'

Tatiana Mukanire, of the national movement of survivors of sexual violence, said she had not seen much progress "because there are thousands of women who have been victims of sexual violence".

The issue is a personal one for the 34-year-old, who was treated by Mukwege after she was raped in 2004.

Her torturer has never been convicted. "That hurts," she said.

She worries for the future of the "little sisters" of Kavumu.

Some will never be able to have children. One brutalised five-year-old "screams when she pisses".

And they may face stigma later in life, with potential in-laws often against sons marrying a woman who has been raped.

Lucie, whose name AFP has changed to protect her identity, is now 12 and at school.

Her mother said European doctors had confirmed Lucie's surgery had been done well.

Adeline, 37, who has eight children, added with relief that she had been told "my little girl could be a mother in the future. We were afraid."

Read Full Story

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Instagram

Google+

YouTube

LinkedIn

RSS